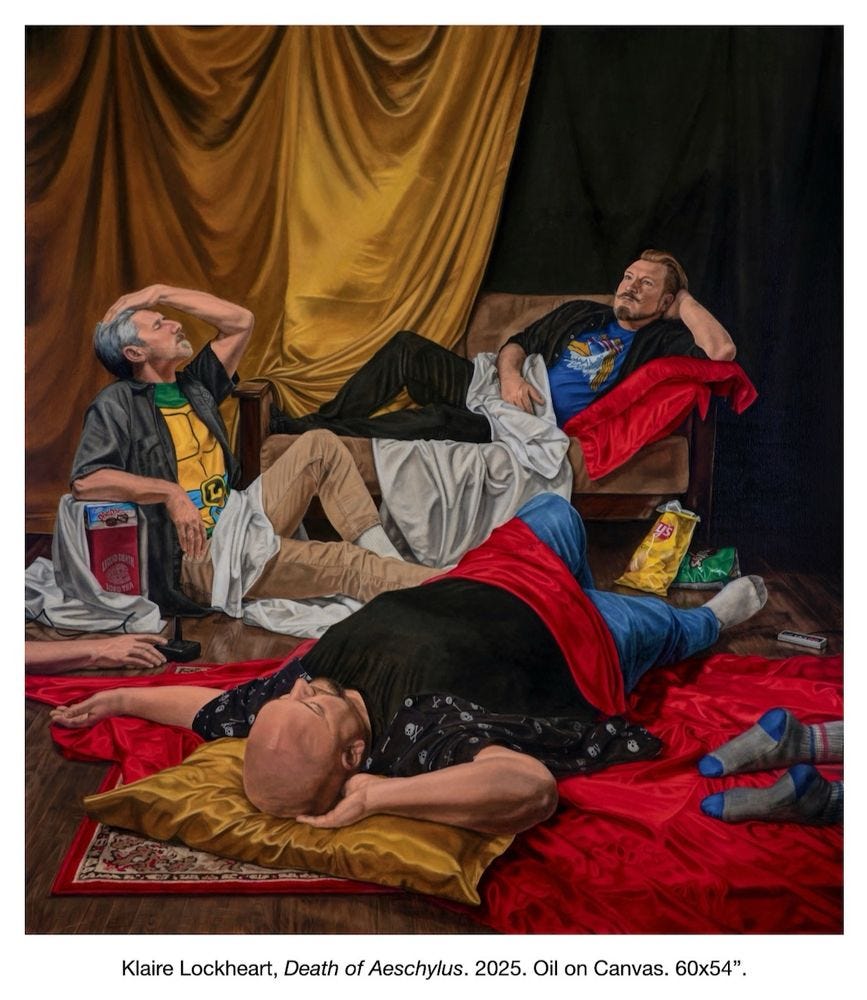

A Reflection on Klaire Lockheart and the Mirror of Our Moment

Because we need all the truth we can get

In the quiet hours when the world feels most contradictory—when empowerment and exhaustion sit side by side like mismatched houseguests—Klaire Lockheart’s art arrives with the strange steadiness of someone holding up a mirror we didn’t realize we’d been avoiding. Trueman might say she paints the present by borrowing the past’s vocabulary; Triola would counter that she stitches the present together from scraps we’ve pretended not to notice. Both would be right.

Lockheart’s portraits, with their deliberate echoes of Renaissance solemnity and Victorian domestic craft, remind us that the old hierarchies never really left. They simply changed clothes. Her figures—armored in lace, poised like saints yet bristling with subversive humor—inhabit the double bind of contemporary femininity with a kind of knowing grace. They are beautiful, but not for our comfort. They are humorous, but not for our relief. They stare back.

And in that returned gaze, we see ourselves: a culture that insists it has moved on from its old scripts while still mouthing the lines. A society that processes its deepest contradictions through irony and satire, as though laughter might be enough to keep the scaffolding from collapsing. Lockheart understands this impulse intimately. Her satire is not a dismissal but a diagnosis—an invitation to recognize the absurdity of the systems we continue to uphold.

“God does not exist, and he is always watching,” matches nicely with the idea that “not everything is political, yet everything IS.”

This link was found on Kalaire’s Bluesky profile page:

There is something quietly radical in her reclamation of the “feminine” as a site of power. Lace, embroidery, domestic craft—these are not quaint relics in her hands but instruments of critique. She elevates what was once dismissed, insisting that the domestic sphere has always been a place of intellectual and political labor. In doing so, she aligns herself with a broader cultural re-evaluation of whose work counts, whose stories endure, and whose hands have shaped the world without acknowledgment.

Perhaps what feels most contemporary in Lockheart’s work is the tension between identity and performance. Her subjects appear costumed, staged, aware of the gaze that defines them. They echo the curated selfhood of our digital age, where authenticity is both demanded and impossible. Yet they also resist. They hold their ground. They remind us that the self is not a performance but something that persists beneath it.

In the end, Lockheart’s art doesn’t flatter. It illuminates. It reveals a culture caught between progress and inheritance, irony and sincerity, empowerment and constraint. It shows us who we are now—not as we wish to be seen, but as we actually stand, in all our contradictions.

And perhaps that is the quiet gift of her work: a mirror held steady long enough for us to recognize ourselves, and maybe, if we’re willing, to imagine something better.