“I’m Your Huckleberry”

A Phrase, a Myth, and the Quiet Accuracy of the American West

For the Trueman–Triola Newsletter

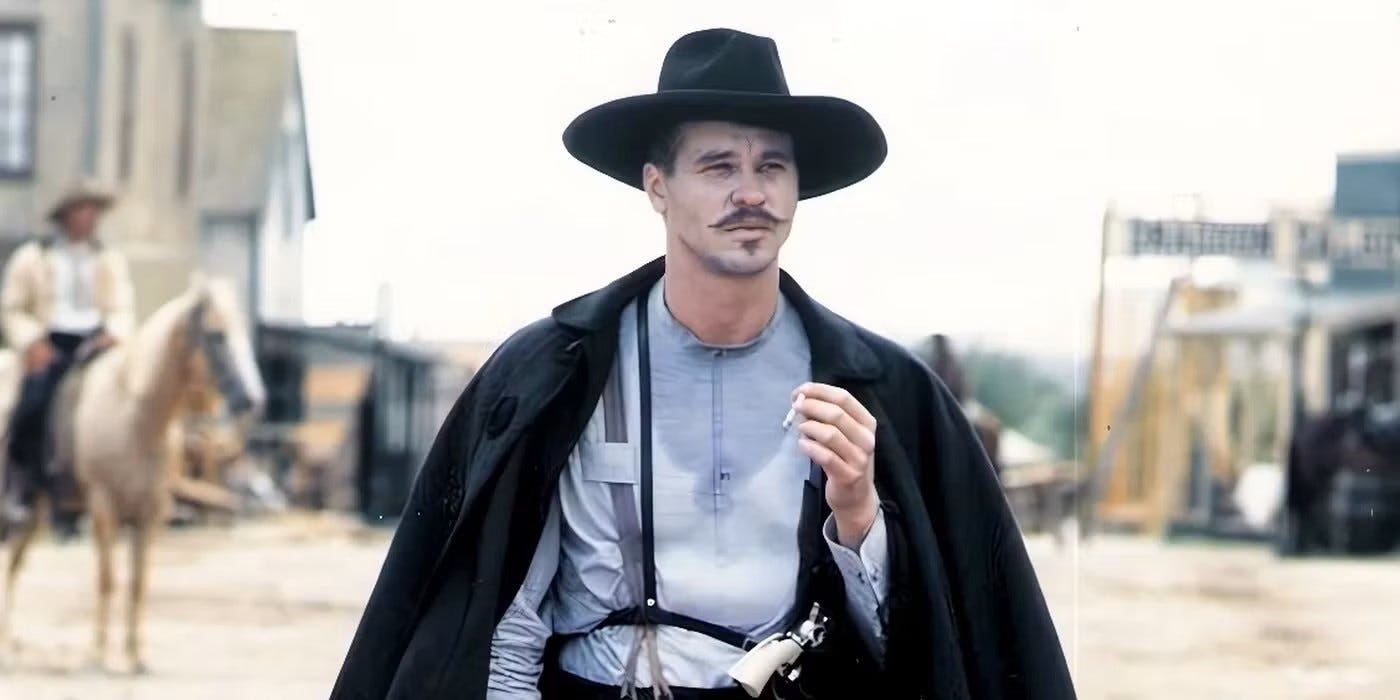

There is a particular pleasure in discovering that a line we assumed was Hollywood invention turns out to be a small, stubborn truth from the American past. Val Kilmer’s now‑canonical delivery of “I’m your huckleberry” in Tombstone has long hovered between folklore and linguistic curiosity, a phrase so perfectly tuned to Doc Holliday’s languid menace that it feels almost too cinematic to be real. Yet the historical record—those brittle newspapers and forgotten poems of the late nineteenth century—tells a different story. The phrase belonged to the era. It was already in the air long before Holliday ever stepped into Arizona.

In the 1870s and 1880s, “I’m your huckleberry” appeared in print with a meaning that feels instantly recognizable: I’m the one you want; I’m your match; I’m the person for this job. It surfaces in an 1877 poem, in an 1881 Nebraska anecdote, in the casual banter of young men and women who understood the phrase as a declaration of readiness, confidence, even flirtation. The idiom was not exotic or coded. It was simply part of the vernacular of a country still inventing itself.

What Tombstone does—what Kilmer does—is restore that idiom to its original register. His Doc Holliday speaks with the languid precision of a man who knows language is a weapon, and the phrase becomes a kind of ethical stance: a willingness to step forward, to meet the moment, to accept the consequences. It is, in its way, a small philosophy of agency.

This is where the line intersects with the broader concerns of the Trueman–Triola project. Both writers—Triola in his analytic dissections of American mythmaking, Trueman in his psychologically intimate portraits of youth—understand that language is never just language. It is a map of the moral imagination. A phrase like “I’m your huckleberry” survives not because it is quaint, but because it captures a posture toward the world: a readiness to be accountable, to stand in the place where one is needed.

The myth that Holliday was saying “huckle bearer,” a supposed reference to coffin handles, is a modern invention—anxious, over‑clever, and unnecessary. Kilmer himself dismisses it. The truth is simpler and more interesting: the line is authentic, and its authenticity reveals something about the texture of American speech at the time, the way ordinary people signaled courage, bravado, or simple willingness.

In resurrecting the phrase, Tombstone did more than craft a memorable moment. It reconnected contemporary audiences with a linguistic artifact of the frontier, a reminder that the past is often stranger, more playful, and more linguistically inventive than we assume. And in that reconnection, the film inadvertently performed the kind of cultural work this newsletter values: the excavation of meaning, the recovery of nuance, the insistence that even small phrases can illuminate the ethical landscapes we inhabit.

Last photo taken of the RL Doc Holliday.