Meaning‑Making, Artistic Agency, and the Aesthetics of Interior Life:

Jackson Pollock, Terry Trueman, and the Artist’s Place in the World

This article examines the intersection of existential meaning‑making, Jackson Pollock’s gestural abstraction, and Terry Trueman’s psychologically interior young adult fiction. It argues that both artists, despite working in radically different media and traditions, articulate a shared philosophical insight: meaning is not inherent in the world but emerges through acts of creative agency. By placing Pollock’s material enactment of meaning alongside Trueman’s narrative exploration of constrained interiority, the article proposes a unified account of the artist’s role as a generator of coherence within conditions of uncertainty. The synthesis positions artistic practice as a model for understanding how individuals construct significance in a world without predetermined purpose.

1. Introduction: Meaning as a Creative Act

Contemporary philosophical discourse increasingly rejects the notion that life possesses intrinsic meaning. Instead, meaning is understood as a human construction, emerging through commitment, interpretation, and creative engagement. This existential framework provides a productive lens for examining the work of artists whose practices foreground the processes through which significance is made rather than discovered. Jackson Pollock’s abstract expressionist canvases and Terry Trueman’s psychologically intimate narratives offer two distinct yet complementary models of meaning‑making. Pollock externalizes the struggle for coherence through gesture and materiality; Trueman internalizes it through the representation of consciousness under constraint. Together, their work illuminates the artist’s place in the world as a figure who demonstrates how meaning arises from the raw materials of lived experience.

2. Pollock and the Materialization of Meaning

Pollock’s drip paintings have long been interpreted as expressions of spontaneity, chaos, or unconscious release. Yet closer analysis reveals a disciplined, intentional practice in which meaning is generated through the artist’s embodied negotiation with paint, gravity, and space. The canvases function not as representations but as events—records of decision, movement, and risk. Pollock’s refusal to rely on inherited forms or traditional composition underscores a central existential claim: meaning is not given but made. His work enacts the process of transforming indeterminate material into coherent form, demonstrating that artistic agency is a mode of world‑making. In this sense, Pollock’s practice becomes a visual analogue for the philosophical argument that meaning emerges through action rather than revelation.

3. Trueman and the Ethics of Interior Meaning‑Making

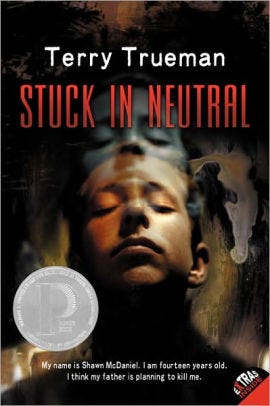

Where Pollock’s art dramatizes the physical act of creation, Trueman’s fiction dramatizes the cognitive and emotional act of constructing meaning under conditions of limitation. His protagonists frequently inhabit constrained circumstances—paralysis, trauma, institutional misunderstanding—yet their interior lives are rendered with depth, dignity, and ethical seriousness. Trueman’s narrative method foregrounds the richness of consciousness even when outward agency is restricted. This emphasis on interiority challenges conventional assumptions about action, suggesting that meaning is not dependent on physical mobility or external achievement. Instead, it arises through perception, reflection, and emotional resilience. Trueman’s work thus extends Pollock’s insight into a different register: if Pollock shows that meaning can be created through radical freedom, Trueman shows that meaning can be created even when freedom is limited.

4. Convergence: Meaning, Agency, and the Artist’s Role

Placing Pollock and Trueman in dialogue reveals a shared philosophical orientation toward meaning‑making. Both artists reject passive models of significance. Both insist that meaning is constructed through engagement—whether with materials, emotions, or the complexities of human consciousness. Their work suggests that the artist’s place in the world is not to illustrate meaning but to model the process by which meaning is generated.

Three points of convergence are especially salient:

4.1. Meaning as Emergent Rather Than Inherent

Pollock’s canvases and Trueman’s narratives both demonstrate that meaning arises through the interplay of intention and contingency. Neither artist treats meaning as a preexisting property of the world; instead, they reveal how significance is shaped through creative negotiation with uncertainty.

4.2. Agency as a Site of Meaning‑Production

Pollock’s gestural agency and Trueman’s interior agency represent two ends of a continuum. Together, they show that agency is not merely physical but cognitive, emotional, and ethical. Meaning emerges wherever agency—of any kind—is exercised.

4.3. Art as a Model for Human Existence

Both bodies of work function as metaphors for the existential condition. Pollock’s canvases visualize the struggle to impose coherence on chaos; Trueman’s narratives articulate the struggle to construct coherence from within. In each case, art becomes a demonstration of how humans create significance in a world that offers no guarantees.

5. Conclusion: The Artist as Meaning‑Maker

The synthesis of Pollock’s material abstraction and Trueman’s interior realism offers a compelling account of the artist’s place in the world. Artists do not merely reflect meaning; they generate it. Their work reveals that meaning is a dynamic, ongoing process—constructed through action, attention, and the courage to confront uncertainty. Pollock shows that meaning can be made through radical invention; Trueman shows that meaning can be made through radical empathy. Together, they illuminate the existential truth that meaning is not a property of life but a practice of living.

In this sense, the artist becomes an exemplar of the human condition: a figure who transforms chaos into coherence, limitation into insight, and experience into form. Through their work, Pollock and Trueman demonstrate that the search for meaning is not a philosophical abstraction but a creative act—one that each person must undertake, and one that art uniquely reveals.