Memories of Emily: The Chair of Intellect

Miss Stul, Isabel, The Cajuns, Fourth Grade

The shelves, overflowing with books, lined an infinite winding corridor of endless knowledge grown from the ether that provided all people with all the wisdom ever needed, not needed, and too much to access, but stood abandoned by those people who let this wondrous place crumble and drag them into the void of the forgotten.

Miss Stul

Drawn back to Miss Stul's display of fruit or homemade cards on her desk, I watched as she fawned in complete surprise when Earl presented her with an apple, again. I didn’t understand this practice but tried to conform by bringing a homemade card expressing my gratitude for Miss Stul’s lessons. I considered bringing fruit since those who brought fruit seemed to get the most attention, but the gratitude list’s mounting debt made me reconsider.

Miss Stul might’ve been a few years older than Marlene, but unlike Marlene, Miss Stul preoccupied herself with the drama and presentation of her lessons rather than the subject matter. Unbuttoning the top of her shirt on hot days, she leaned across the desks, resembling a supermodel at a photo shoot. Her pedagogical practices drew the nuns’ ire I once heard voiced, “Button your blouse. That’s too provocative for young boys.”

Perhaps they were right. I found myself more attentive on days her breasts shimmered through her shirt’s top or when her skirt’s height allowed easier visual access when she posed on the desk. Yet, increased attention neither improved learning nor reduced the struggle to achieve in Miss Stul’s classes.

Finished dramatizing her presents, Miss Stul began lecturing like a lead actress giving a Broadway soliloquy. “The US leads the free world because our country allows for kids to grow up and become anything they want.” She pirouetted and pointed to a student in the audience. “If you choose to be the president, and you work hard, you can become the president. That's called the American Dream.” She finished, appearing to wait for a standing ovation.

Receiving smiles and adoration from Earl and his cronies, she dispensed our graded quizzes taken the previous day. “Here are your quizzes. Now, let’s go over the answers.”

Staring at the geography quiz, which asked us to list the seven continents, I puzzled over receiving a C, believing the answers correct.

“Earl, Amy, and Billy all got a hundred percent on the quiz.” Miss Stul announced the students with perfect scores, so I waited until the end of the day to approach her, not wanting to be made fun of by Earl and friends.

“Miss Stul, why did I get a C? Aren’t these the right answers?”

She took the quiz from me. “Are these the right answers, not aren’t. Yes, the answers are correct, but you misspelled three of them. Part of knowing the right answer is being able to write or pronounce it correctly.” She handed the quiz back to me.

Exiting the building, I felt a candy bar wrapper in my pocket and tossed it into the waste bin by the door but stopped walking when I noticed Earl’s quiz resting in the trash. Retrieving his test, I took it home to verify the answers using my trusty dictionary and found Earl misspelled two of the continents.

Isabel

Isabel only spoke to me once. Like my grandfather, she spoke the language of the silent that effuses meaning from a syntax of disposition. Never once did Isabel stand in the group laughing or uttering “molasses,” “ugly,” or “fag.”

Somewhere in the fourth grade, I heard one of the girls yelling as Earl prowled the schoolyard pulling girl’s skirts up. Watching him until he got to Isabel, I dashed across the playground and jumped on Earl’s back, but being skinny and weak, he easily threw me to the ground. “You startin’ with me molasses? Wanna fight, huh — come on.”

The ice bag cooled my stinging eye and bruised jaw, but the lump hurt worse as it gnawed at my throat for release. Amidst combat with the lump, Isabel entered the nurse’s office, taking a seat across from me in her ruffled uniform that revealed her scraped knee. She looked at me sadly. “Thanks.”

The lump was gone.

Just as I always imagined, Isabel and I would marry. Having proven myself the heroic knight who saved her from the wrath of Earl assured togetherness. Losing the fight and receiving an ass whipping from my stepfather did not dim thinking on this matter — she loves me.

My belief never actualized since Isabel moved back to Puerto Rico shortly after the fight. Miss Stul announced Isabel’s leaving to the class, and the students signed and presented a large farewell card on her last day. The next day, I sat on the wall in the playground’s corner and stared at the ground. With Isabel gone, all that remained was Earl and the war with the lump.

The Cajuns

Mount St. Helens erupted on May eighteenth, 1980: an event causing much fear to stay with my stepfather’s parents in Dupont, Washington, starting June first. The trip resulted from my parents traveling abroad, which never made sense since my parents discontinued babysitters after Marlene. Sitting at home alone on weekends seemed no different than sitting home alone on summer days. Summer days might have been less scary than sitting alone in the house on a Saturday night watching television, jumping at every creak and moan of the house. Although reluctant, the trip proved enjoyable.

Arriving in Washington State, my step-grandparents picked me up from the airport, and the drive to the house blurred in a new scenery as the conversation provided more information about family, which despite being a member, no one ever discussed with me other than the Baltimorons, whom I no longer saw. Similar to the Baltimorons, a language barrier needed overcoming. They were Cajuns from Louisiana who spoke the language of Cajun or Creole, which I never knew for sure the difference since they used the terms interchangeably. Adding to this complicated lexicon, they also spoke English and French combined with Creole into their personal trilingual vernacular. My Cajun grandfather looked at my Cajun grandmother as he drove. “Baby, he doesn’t understand you because he’s white.”

“Ouais.”

I leaned forward in the backseat. “I’m a quarter Indian, a quarter German, and half WOP.”

My grandmother, who was half-something-unknown and half-black, looked in the backseat and frowned at me. “Hmm. You’re whiter than you are Indian. Are you sure you’re Indian?”

My grandfather looked over his shoulder for a second. “Your hair’s kind of nappy but more curly. I thought Indians had straighter hair? Well, it doesn’t matter. No one is going to be confusing you for black, but I wouldn’t go joinin’ the Klan either.”

A few days of confusion and practice gained a rudimentary understanding of their language, allowing adequate translation of my grandmother, whose speech presented more difficulty than my grandfather. “Manman ou se yon fanm blan,” became, “Ta mère est une femme blanche,” translating to, “You mother is a white woman.”

The need to categorize by race, gender, and nationality when meeting new groups or persons became clear by this point in life. Social taxonomical importance even overrode fear of the recently erupted volcano that covered everything with ash, and in my mind, threatened to make Washington the next Pompei as depicted on the episode of In Search Of seen just before this trip. Perhaps my teachers and parents were correct in their assertions of my stupidity because this confusing, often contradictory labelling eluded my understanding.

I was assigned my stepfather’s old room, which appeared to be no different than when he left. Time stopped in the room near the end of his senior year of high school, evidenced by his diploma, posters, magazines, books, and sports relics. Unable to reconcile the room’s adolescence with my stepfather’s persona, his past presence in this room seemed unbelievable if not for the trophies lining the shelves bearing his name. My bookshelves displayed no awards commemorating long-forgotten competitions, and these trophies stood like guardians barring entry to a place with no meaning.

The Mad magazines stacked by the shelves of trophies stopped in 1961. Reading the magazines late into the night while the black and white television played the rerun of Star Trek: Spock’s Brain, I tried to control the bedwetting. In the early morning hours, the static of the signed-off channel woke me, and the trophies peered from the shelves in the light of the television. My action figures rested in their carrying case at the foot of the bed, and I wondered why my stepfather never took his trophies with him. I would never leave my action figures behind.

My grandfather fought in every war since World War II and won them all, and while retired from the Army, he still worked at Fort Lewis as a civilian. Like my uncle Cain, my grandfather’s eyes held that distant stare, but the vacantness of my grandfather’s eyes appeared tamed like a trained tiger. His military bearing remained constant in his gesticulation, lingo, and treatment of life in a jovial way, but his lens of life focused and deduced solutions through war-infused wisdom.

“Now, Bo, you need to understand guns solve many problems. If you need to protect your house, you get a gun. If someone is hurting you, a gun will stop them. Ain’t never been a war won without a gun.”

I received my first BB gun and firearms lessons from my grandfather. “Guns are nothing to take lightly. More people get killed by their own guns than by stranger’s guns. There are some rules you need to know about guns. The first rule: don’t ever point a gun at someone unless you intend to kill that person. The second rule: you never play with a gun. Guns are serious business and not toys. The third and most important rule: when the heat is on, you don’t hesitate to pull that trigger cause if you ain’t quick — you’re dead.”

My grandfather gave me a shoulder holster for a toy thirty-eight he bought me that looked just like the ones cops used on TV. Many a day passed in the yard, practicing marksmanship and listening to my grandfather tell stories. Filled with special tobacco sold to him by a friend on the Indian reservation, his pipe smoldered as he leaned back in his lawn chair and philosophized life and war.

“Bo, you got to understand that life can be tough, but you got to choose the right roads even if that makes life harder sometimes. In 1943, I had to choose whether I was going to serve in the Army in the 429th Medical Ambulance Battalion or if I was going to serve with the all-black 761st Tank Battalion. The Army told me the only way I could serve with the 761st was if I took a pay and rank reduction from first-sergeant to private. Even though the loss of money hurt, I did it to serve alongside the blacks fighting. You know why?”

I shook my head.

“In 1943, if I got on a bus to go across town, I had to give up my seat to any white person needing it. We were forced to prove to the Army, Patton, and all white people that we could fight those krauts just as hard if not better than the whites.”

“Did you shoot them?”

“We unleashed holy hell on those Nazi sons of bitches. I had a fifty-caliber machine gun mounted on my tank, and I used it to mow those bastards down. White southerners were bad, but the Nazis were far worse. They were all business about killing everyone who wasn’t a white German.”

His strength and seeming invincibility cascaded over me in his discussions of war. Retiring to bed at night, I hung my plastic .38 on the shelf, leaned my BB gun in the corner, and slept easy. I rose in the morning dry as a bone.

Like my Baltimoron grandmother, my Cajun grandmother spoke the culinary language, wielding fluently the Cajun vernacular of gumbo, shrimp étouffée, jambalaya, corn maque choux, and other foods I couldn’t pronounce. Cooking and drinking iced tea mixed with something from a bottle hid behind canned foods in the cabinet, she filled the house with her multilingual lyrics by midday, which made no sense to me but was nice to listen to. Sometimes while cooking, she asked questions about my mother and seemed more ill-informed of my parents than me. “Where is your mother from? What does she do for a living?” Not understanding my mother’s job beyond being a manager or boss, I provided the best answers possible, which my grandmother nodded and seemed to accept.

Discussions often pertained to my stepfather. “Bo, your stepfather doesn’t come home hardly ever. He has an important job that keeps him away. Your mother should be glad he takes care of her and helps her improve herself. Most divorced working mothers are not so lucky.”

Once, my grandmother took me to an old, abandoned high school. The large, lonely brick building still looked ready for students except for the large chain and lock hanging on the front door and unkempt lawn surrounding. Behind the school, wild strawberries grew along a fence separating the overgrown athletic fields from the school, and we picked the berries filling several large bags.

She handed me a bag. “Bo, your stepfather went to high school here. The school shut down years ago, but it used to be a nice school. We used to come here and watch him play sports. He was good at sports. That seems so long ago. I guess it was. You know you’re only a kid once, and you only have one home. Everyone grows up, but you never grow out of your home. You should always come home from time to time.”

My grandmother sighed and stared beyond the fence, forcing a fight with the lump until we left. At the house, we washed the strawberries for cooking before crushing them in a bowl. When ready, we poured the mash into a saucepan, mixing sugar, lemon, and other ingredients. Stirring the mixture, watching the sugar melt slowly, my dislike for my stepfather simmered into complete despise.

A family living a few blocks away visited my grandparents for a barbecue one Saturday afternoon, and on this occasion, I met Ray. Upon meeting the family, the overt need to classify everyone by race and nationality passed in the obviousness of Ray’s dad being a tall, black military man who spoke Creole like my grandparents, and Ray’s mom being a small Vietnamese woman. Ray and I sat in the yard discussing Star Wars as the adults smoked my grandfather’s special tobacco, holding lively discussions of Louisiana and Vietnam. Ray displayed no animosity, and we got along well, sharing an affinity for action figures and the military, which led to our working together on weekdays.

After the barbeque, we played together at my grandparents’ home. Exiting his father’s car in the mornings, Ray appeared on his way to work, walking towards the front door carrying his Star Wars action figure case as if prepared for a day at the office. Meeting Ray at the door, we began our important action-figure-work in the front yard.

Ray held extensive knowledge of the military’s history and mechanics, which he used to clarify the confusion of his father calling my grandfather "Chief" and my grandfather saying "Top" when referring to Ray’s father. “Oh, Top, means First Sergeant and Chief is sort of like callin’ someone sir. Chiefs are warrant officers. They’re between officers and enlisted men.”

He spoke much like my grandfather. “See, the stormtroopers are enlisted men in the Army of the Empire. Darth Vader is like a five-star general. Now, the rebels are like the American’s fighting for freedom against the Commie Soviets. Each side has its own outfits like infantry and artillerymen…”

In exchange for Ray’s military knowledge, I taught him the secret of obtaining action figures for free. Stumbling into the secret occurred at summer’s beginning when I purchased a new stormtrooper action figure and found his hand broken. My grandfather donned his glasses to examine the toy. “You just got this action figure. Look on the back of the package and see if there’s a warranty.”

Doing as he said, I discovered the warranty, which required sending the toy company, Kenner, the broken figure and a letter explaining the problem. I wrote the letter but forgot to include the damaged stormtrooper, and miraculously, they sent me a whole new stormtrooper leading to peaceful days of Ray and I writing letters to Kenner or battling the Empire in the yard.

The summer passed in peace, mostly. One day sitting in the front yard writing letters with Ray, some older neighborhood kids rode their bikes towards us on the sidewalk. They stopped in front of us and said something I didn’t hear but then biked back and forth on the sidewalk, calling us names. Ray and I gathered action figures and letters as the pack of kids swarmed the sidewalk calling Ray a nappy-head, me a fag, and both of us sissies. Just as we headed to the front door, my grandmother exited the house holding a rifle.

Walking with a purpose to the sidewalk, she turned a sharp left face into the path of the largest kid racing on his bike. Lifting the rifle over her right shoulder, she butt-stroked the boy in the chest as he attempted to pass her. Hurled from the Huffy's banana seat, he hit the earth as the bike veered from the sidewalk and collapsed in the street. She stood over the fallen boy, rifle at her ready. “Go on! Get up. Get your bike, and get the hell out of here.”

The boys rushed home and told their parents, who came to the house with the Sheriff following. My grandfather came home from work early, and arguing ensued between the adults and the Sheriff. Ending the confrontation after a few minutes, the Sheriff said, “The boys were just being boys, and you had no right to butt-stroke anyone. However, those boys were trespassing since you own the sidewalk in front of your home. I think we should all just learn something from the incident and call it a day.”

Everyone agreed, and the Sheriff left. My grandmother entered the house where Ray and I waited in the living room. “You boys need to learn to not take crap off other people. You got the same right to walk down the street as them other boys and certainly have the right to sit in your own yard. Don’t let people control you, especially not in your own yard.”

My Cajun grandfather left early to work at Fort Lewis daily, but on days off, he and my grandmother took me many places. We ate at the revolving restaurant in the Space Needle, visited the Indian reservation, went to a wildlife park to see the endangered buffalo, and once, we drove near Mt. St. Helens.

We parked on the side of a closed road and walked past the signs and barriers blocking access to an area once connected by a bridge. The steel bridge that spanned the waterway now rested twisted, half-buried in the muddy ravine, appearing as if a titan punched it into the earth. My grandfather nudged me. “Bo, there is an important truth seen in the volcano. Look around at all this destruction. People will point to this catastrophe and tell you things like, ‘The volcano destroyed this bridge but filled this river creating new land for plants and animals to thrive. Destruction and creation are like air and water. We need both, and neither can exist without the other. Not all destruction is bad and not all creation is good.’”

I nodded as he turned to me, wrinkling his brow with sternness.

“Bo, that’s all bullshit. The Man says things like that, trying to smooth bad situations, or worse yet, trying to fool us. The earth moves of its own accord, and we just happen to be living on it. What destroyed this bridge and killed people on this mountain was ignorance and arrogance. You know about Pompeii?”

I nodded.

“Good. Then you know building a road or house on an active volcano is a bad idea, and if you do it and your house gets destroyed, it’s because you built it on a volcano. There’s no marriage of destruction with creation, there is no marriage of bad with the good, and that means there’s no significance behind bad acts other than them being bad. No deeper meaning necessitated the enslavement of millions of blacks, the killing of millions of Jews, and the destruction of unknown numbers of Indians. Ask yourself this: what meaning or great lesson was so important it needed the enslavement of millions of Africans to learn? Nothing. The lack of meaning was already there in the history of the Greeks, Romans, Mongols, the Americas, and countless other nations that practiced mass slavery and genocide. If there’s any meaning to be had, it’s that all these civilizations repeated the same evils and fell.”

My grandfather grasped my shoulder. “The truly wise don’t apply meaning to the meaningless. The Man does that to hide his motives, and if you’re not wise to this fact, you’ll find yourself fighting a meaningless war.”

As we walked away from the destruction, I looked back and saw a sparrow land on the twisted metal jutting from the dead landscape, either unaware or not understanding the devastation surrounding him.

Shortly after returning home at the end of summer, I ate dinner with my mother one evening when my stepfather worked late. Sitting across from me at the dining room table, she acted unusually curious. “So where did you go in Washington?”

I told her about the Space Needle and other places.

“Did you all talk about us, your stepfather and me?”

I related my grandmother’s belief in my mother’s luck for having my stepfather care for her and helping her improve herself as a divorced working mother. Rising from her seat, she stepped the length of the table and screamed as she slapped my plate off the table. “I don’t need anyone taking care of me! Improve me — that old bat needs to get out of the fifties. Just remember who took care of you when your father left.” Slapping my face. “Clean that shit up!”

My stepfather arrived as I picked peas out of the carpet, and after trading words with my mother, he grabbed the back of my shirt, stretching it above my head, lifting me to my feet, dragging me through the house. “Why are you so fucking stupid? Why would you say something like that to your mother?”

Before I could answer, he threw me into my room. They yelled in the dining room, but I couldn’t discern their words. Not knowing what I said wrong, I waited for my stepfather’s. He didn’t return, and somewhere in the night, the house went silent, allowing a restless sleep before pissing the bed, which couldn’t be controlled anymore.

Fourth Grade

Humanity paid an enormous toll of lives in the Az invasion, evidenced by the orphaned refugees amassing in the backyard of my dead adopted parents’ home. Helping the wounded from the bus, I ordered some of the Chromag children to find water and supplies while Emily treated many wounds. Sadly, some of the Chromag children wounded in the crossfire didn’t survive. Finding Isabel’s lifeless body slumped in a seat and carrying her from the school bus made my heart sink. She was a bright light in the primitive cave of the Chromags.

Shoveling dirt, I prepared the graves for the fallen and mumbled something Christian as I filled their plots. Dropping to one knee, swearing vengeance, I looked across the landscape littered with spaceship and fighter jet wreckage. Where the elm tree once stood, a crashed Az ship glinted in the sunlight, drawing my eye to Emily waving from atop the alien craft. Running across the yard, I joined her as she stared into a deep, winding cavern unearthed by the crashed ship. “I can’t believe it. It’s been right here the whole time.”

Ironically, the invading force’s attempt to destroy humanity unearthed the Great City of Atlantis, which not only ended our search but held the salvation from the Az. Ordering the refugees to stay behind, Emily took my hand, leading me down the cavern that filled us with much dread and anticipation of our people’s fate.

Entering the great city that withstood the ages revealed the technology and great halls of the Old Republic still intact but silent and dark with secrets. Walking the abandoned halls of the ghostly city, I turned to Emily. “Too much time has passed. It would take us too long to research and read the generations of history.”

Emily nodded. “We’ll use the Chair of Intellect.”

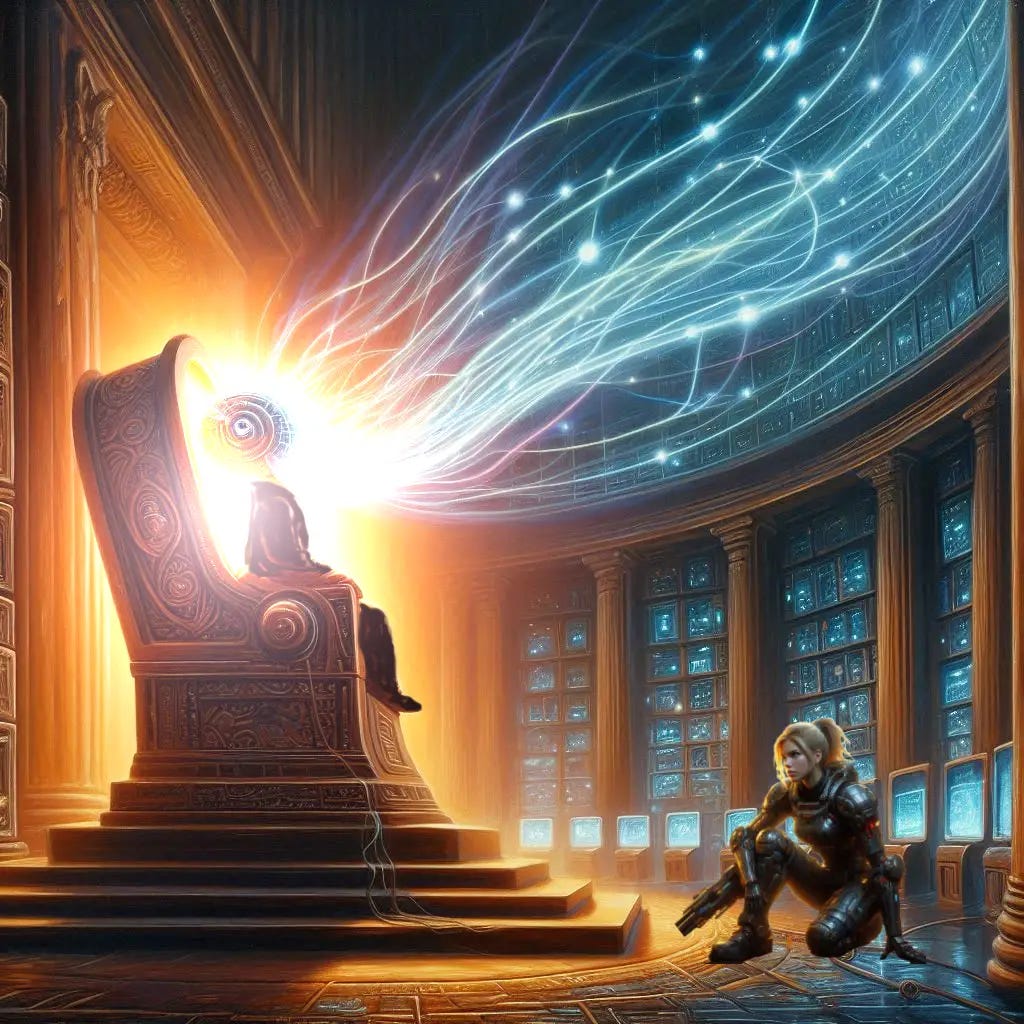

We made our way to the Hall of Knowledge and found ourselves before the large, ancient chair with a helmet meant to lower onto the occupant’s head. Emily turned on the power, and the room flashed with light as massive computer databanks teemed with information. Looking back at Emily once, I sat in the chair, which glowed with electrical life as the helmet lowered and caused a dreamy state, infusing knowledge.

Pyroclastic bursts: volcanic might

Standing on the slope: fists in plight

“I cannot win; I’m never right

“They say I sin, but I start no fight

“I can’t live this way another night”

Hearing me in desperate plight

The shining star; the guiding light

She appeared pure, just, and right

Emily revealed wisdom’s sight

Touched my brow, speaking bright,

Let not the liars fill your head

Fork not your thoughts with lies you’re fed

Listen to my voice, my song instead

Follow me, and you shall not dread

Follow me, the true path to tread.

Slowly awakening revealed Emily beside me opening her eyes to the knowledge unwinding in our minds as the Chair of Intellect gifted and cursed us with the truth. Gathering ourselves, we sat upon the steps of the Hall of Knowledge and ruminated our sordid history.

After becoming lost in space and presumed dead, West Atlantis struggled in the passing millennium. The isolating principles the Atlanteans held dear proved to be their undoing as a lack of new diverse thought and genetics diminished the social and biological strength of the Atlantean evolution. Moving the city again, with seemingly good intentions to separate further from humans, isolated the Atlanteans, causing a social, physical, and mental decline. Their bodies, lacking the challenge and benefit of a diverse environment, became susceptible to new diseases, withering the Atlanteans in a plague caused by their unwillingness to change and accept others.

The Chromag children slowly gathered at the bottom of the stairs, having not listened and followed us. Seeing them, Emily stood, fist raised to the sky. “We were the Atlanteans! The progenitors of democracy and the first true advocates of equality. What began as a great experiment in the Old Republic flourished and raised these halls in the splendor and power of freethought. But in our achievement, we failed, having committed the sin of arrogance.

“While we dined in our halls, enjoyed our fancy technology, and discoursed the finer points of politics — people suffered. While conquerors standardized, institutionalized, and mechanized slavery, and genocide, the Atlanteans held picnics and abstractedly spoke of the atrocities.

“We paid a heavy toll for our mistakes. Coveting knowledge turned to hoarding its benefits. The application of liberty and justice became veiled in defending the right to hate. The love and protection of all people turned to isolation and despise as we spit the words Chromag and human. In our arrogance, nature reclaimed us, for that which cannot change — shall perish.

“We were the Atlanteans, but today we are all Atlanteans, for Atlantis is for everyone, or it is for no one.”

The noble city, that waited a millennium for its new citizens, filled with cheers. Emily’s magnificence and brilliance stole the hearts of the new Atlanteans but most of all mine. That day began the honorable task of teaching and guiding the children of Atlantis, who took turns sitting in the Chair of Intellect where we filled them with the knowledge necessary to win the war with the Az. More importantly, we educated them to form the culture and civilization the world needed. To be the exponents of justice and liberty. To defend the weak and free the oppressed. To be the true Atlanteans.