Reflection: On the Mind’s Cruel Little Juxtapositions

Courtesy of @tetrismegistus.bsky.social

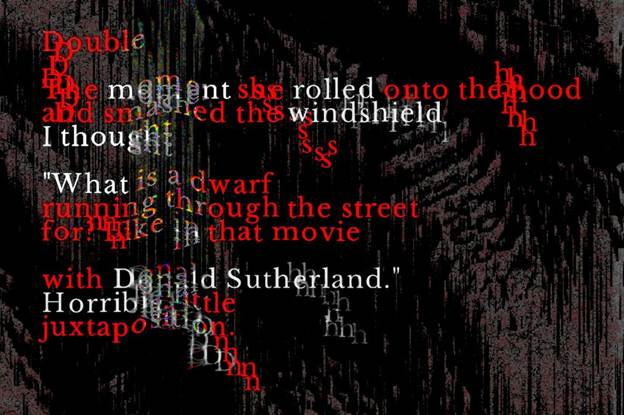

Double The moment she rolled onto the hood and smashed the windshield I thought “What is a dwarf running through the street for? Like in that movie with Donald Sutherland.” Horrible little juxtaposition.

Cruel Little Juxtapositions

There are moments when the mind betrays us—not out of malice, but out of its own strange, associative machinery. A body rolls across the hood of a car, glass erupts into a spiderweb of fractures, and before the moral self can even rise to attention, some half‑buried cinematic memory leaps forward. A dwarf running through a street. Donald Sutherland. A scene you didn’t ask for, didn’t summon, didn’t want. And suddenly the real and the remembered sit side by side like mismatched bookends.

This is the kind of moment the Trueman–Triola sensibility lingers on: the ethical vertigo of being human. The way the mind, in its speed, can be grotesquely inappropriate, even as the heart is horrified. It’s not cruelty—it’s the brain’s reflexive filing system, grabbing whatever image is nearest in the dark.

Just Weighing.com

What unsettles us is not the accident itself, but the recognition that our interior life is not fully under our jurisdiction. We like to imagine ourselves as coherent moral agents, narrators with editorial control. But then a woman hits a windshield and some absurd, irrelevant film clip pops up like an uninvited guest. The juxtaposition is awful precisely because it reveals the gap between who we aspire to be and the chaotic, uncurated archive we actually carry around.

Triola would say this is the mind’s way of measuring catastrophe in seconds—how trauma compresses time, how memory intrudes without permission. Trueman would notice the ethical tremor beneath it: the shame of the involuntary thought, the sudden awareness that empathy is not always instantaneous, that sometimes it must catch up to the speed of impact.

unnar.uchte @uchte.bsky.social

And maybe that’s the point. The moment is not about the joke—there is no joke. It’s about the shock of seeing your own mind misfire in the presence of suffering. It’s about the recognition that being human means living with these collisions of the sacred and the absurd, the tragic and the trivial, the real and the remembered.

The road never ends, Ryan wrote (The Kid Who Killed Cole Hart—Trueman, Latah Books, 2015). And maybe this is part of what he meant: that we carry every image we’ve ever seen, every film, every stray association, and sometimes they surface at the worst possible moment. Not to mock the world, but to remind us that consciousness is a messy, ungovernable thing.

The work—the ethical work—is what comes after the juxtaposition. The moment when the heart catches up, when the mind stops scrambling for metaphors and finally sees the person in front of you. The moment when the absurd dissolves and the human remains.