Blossoming like a flower in the spring, the language of all things grew from the ether in an alphabet of endless letters forming infinite language conversable amongst all people, animals, and things, answering all questions perfectly but ceased when all the unanchored letters and words passed into the void of the forgotten.

“The words won’t write themselves.” Miss Vyne’s voice broke my attention.

My stare returned from Isabel in the yard beyond the window to the phonics assignment I would’ve finished during class if not for Earl and others shooting spitballs or making faces when Miss Vyne turned her back to write on the board. Now, a constant aggravation by third grade.

“Being lazy is going to get you in trouble because lazy people become ditch diggers and criminals. Is that what you want?”

Sick of the scolding, losing recess time, and being punished, I employed my uncle’s fighting lesson and stood up for myself, unleashing the truth. Perhaps I sank to the rank of tattletale, and maybe I confirmed my sissyhood, but something needed to change. I told Miss Vyne everything about Earl and the other kids’ torment and how none of them ever received punishment.

Miss Vyne listened, and when I finished, she pointed her pen. “You have it very easy compared to me. When I went to school, we were held to a much higher standard. We were expected to be good Christians, and being a good Christian is about taking responsibility for yourself and not blaming other people for your mistakes. Good Christian men take responsibility for their actions. Your problem isn’t with other kids; it’s with yourself. Earl and some of the other children are shining examples of strong boys who will be good Christian men. One day, when you can’t find a job, people like Earl are going to be the good Christians who give you work because they’re charitable.”

I stared into my phonics booklet.

“Just remember what I said when you find yourself on skid row and you look up to find you’re begging a quarter from Earl.”

That conversation bothered me the rest of the day, making concentration impossible even when sitting in my room at home. Later, I watched television and couldn’t remember whether I watched Logan’s Run or Battle Star Galactica. Lying in bed that night, I fought the lump a long time before falling asleep to piss the bed.

Klutz

With the same importance of the gratitude ledger providing a necessary daily reminder of all I owed to my parents, they believed in reminding me of every indiscretion committed.

“Bo, are you going to hurt your mother’s feeling like you did that time you came home from your grandparents?”

“Bo, do you really want to upset your father like the time you bothered him about television?”

“Bo, are we going to have a repeat of the time you embarrassed us on the boat?”

The most atrocious mistakes permanently branded, like spilling a glass of soda at dinner, which deemed me a klutz from that day forward.

“Bo, are you sure you can carry that bag of groceries; you know you’re a klutz?”

“Bo scraped his knee playing in the yard, just like the klutz he is.”

“The klutz slipped on the ice getting in the car.”

Along with klutz and other names, my parents branded me a liar. Early one morning, I went to the kitchen to get something to eat and pulled the bread off the toaster, where it was stored, and toasted two slices of bread. Not thinking, I pulled the toast from the machine and returned the bread bag to the top of the toaster.

Smelling plastic melting, I quickly grabbed the bread from the toaster but not before ruining the bread. Panicked and fearing an ass beating, I tossed the bread in the trash, hoping no one would notice. Roused from sleep by the burnt plastic smell, my mother discovered the missing bread and confronted me with the situation. I denied any involvement, lying as if my life depended on it since I felt it did. My mother confirmed my fear, slapping my face. “Bo’s a liar. Lying Bo! Bo lies. That’s what you are, a liar.”

From that day forward, I had no credibility.

“Bo, I might be willing to believe that people are bothering you at school, but you know how liars exaggerate things.”

“Bo, are you sure you did your homework? I can’t tell because you lie, Bo.”

“Bo, maybe people are mean to you because you lie. Nobody likes a liar, Bo.”

My mother added the cost of a loaf of bread to the ledger, and many times I stared at that ledger, amazed by that bag of bread’s tremendous cost.

Somewhere in the third grade, I came home with a black eye, and my mother told me to play sports with the other kids, so they would stop thinking of me as a wimp. Her argument seemed weak since she also referred to me as a klutz. This characterization, combined with my lack of sports knowledge, and my stepfather’s view of me being a pansy, precluded any reason for me to attempt playing sports. But desperation drove pursuit of my mother’s advice, and I asked my stepfather to teach me sports.

As a football player, college wrestler, gymnast, blackbelt, and (of all things) a ballroom dancer, he possessed an abundance of athletic experience. Surely, he would impart some sport’s knowledge to his stepson. He agreed to assist, decided on baseball, and we assembled in the yard with gloves and ball. “Put your hand in the glove, like this. Right. Now, you catch the ball here in the glove. Now, move back about ten feet.”

We threw the ball back and forth, progressively increasing distance between us, which progressed well until he pitched high, sending me racing backward, positioning to catch, but missing the glove's mouth, the ball struck and burst my upper lip. I knelt, holding the bloody lip as my stepfather approached, shaking his head. “Bo, you can’t be scared of the damn ball. I don’t have time for this nonsense, Bo. Now get up and try again, Bo, or learn on your own, Bo.”

I stood but not fast enough to stop him from throwing the glove at my feet and walking off in disgust, making that the only time my stepfather and I ever played sports.

My mother added the cost of my stepfather’s time to the ledger, so I took a less expensive approach to sports by participating with the other kids. Logically, people could learn sports by participating, so I just needed to show my classmates a willingness to learn, and they would teach me.

On Monday, I joined the boys at recess for basketball and waited for team selection. To my surprise, Earl allowed participation, despite concerns for my ugliness and faggotry. I managed to be picked for a team and soon played with no understanding of the game beyond running up down the court trying to throw a ball in the hoop and shouting for someone to pass me the ball. Someone finally threw me the ball, and in a glorious moment of smacking the ball instead of dribbling, one foot hit the other launching me into the air. With the ball locked in my hands, my face collided with the ball as it hit the ground, bursting my nose into a bloody mess. Humiliation seared my face seeing Isabel turn away just beyond the circling kids that roared with laughter.

Having in one week incurred a busted lip, a bloody nose, and a black eye, I quit the dream of sports and returned to the wall to observe from afar. My lip and nose pulsed as an escaped basketball rolled past, followed by Earl retrieving the ball. “You suck at basketball.”

I couldn’t argue this fact, but I excelled at fighting the lump.

Marlene

From the front door of my parents’ home, the road sat about thirty feet, and a cornfield beyond stretched on forever. From the back door, grass spread for an acre until reaching an old elm tree separating my parents’ property from the neighbor’s farm beyond. Our neighbor, a retired farmer, owned a large barn that no longer boarded animals since the barn retired with him. The massive barn appeared like an antique photo, and I spent many quiet summer days in the yard watching pheasant run around the old barn.

Summer provided a reprieve from school, but living in a rural area made visiting places daily impossible with no stores within walking distance and with my parents working. To pass the time, I watched TV or sat in the backyard reading or playing with toys.

If kids my age lived nearby, I didn’t know them, and babysitters became my contact with the world. Most babysitters arrived in the morning and talked on the phone all day, and sometimes invited one of their friends over to help pass the time until my parents returned home. The girls were pleasant, providing I didn’t interrupt their conversations, and they went about the task of babysitting efficiently and unremarkably.

Of all the babysitters, I remembered only Marlene. She entered life on Sunday, July 8, 1979: a date committed to memory because, on July 11, 1979, Skylab fell from space while Marlene and I watched. On Sunday evening, she arrived carrying a stack of books under one arm and a large bag of clothes in the other. She was a pretty girl who wore her brown hair in braids, which gave her a very natural look, but her choice to wear sandals with denim skirts and tube tops drew my stepfather’s condescension as she walked to the house from her station wagon in the driveway. “The hippy girl is here to watch you.”

Marlene entered the house, and my parents hastily introduced her as they exited the front door to catch their flight. Holding her books and bag, appearing surprised by the quick introduction, she smiled at me curiously. “Snacks. I have Tastykakes.” She fished some peanut butter Kandy Kakes from her bag as I nodded, acknowledging the total coolness of this hippie chick. We ate Tastykakes and watched Hardy Boys-Nancy Drew Mysteries: Search For Atlantis before going to bed.

Burnt eggs and bacon smoke drifted into the bedroom, stirring me from sleep. Rising to investigate, I found Marlene cursing under her breath as she shoved a frying pan around on the electric burner while performing a ballet, avoiding hot grease popping from the stove to her bare feet. She turned the stove off and twirled, looking for something as the spatula she held dripped grease. Noticing me stopped her action, and she laughed, “I’m sorry. I’m not a very good cook. How about waffles? I think I saw waffles in the freezer.”

I nodded and helped her find the waffles. Soon, we sat at the dining room table discussing the day’s itinerary as she filled waffle pockets with syrup. “So, what do you want to do today?”

The question seemed alien or nonsensical, so I shrugged, cutting a waffle with a fork. “I don’t know.”

“Well, what do you normally do during summer break?”

I related my expertise in television viewing and book reading prowess. I explained my cinematic skill and how sometimes my parents dropped me off at the movie theatre for the whole day. She nodded, appearing genuinely interested and impressed by my abilities, so I showed her my collection of Star Wars action figures. After listening to the action figure lecture, she stacked our empty plates as I packed up the figures. “Don’t you have any friends?”

“No.”

Marlene sat back, looking at me thoughtfully. “I know; let’s go to the pool at the Lion’s Club. That’ll be fun.”

Although not enthusiastic about the prospect of a pool, a club for lions held tremendous appeal. Marlene told me to put on my bathing suit, and when ready, I found her in the kitchen packing Tastykakes, books, and towels in her bag. “Wow, you’re fast. You must be excited to go to the pool.”

“I’ve never seen the lions.”

She frowned. “Yeah, you’ll like the Lion’s Club. Ok, now we’re ready.”

We left the house, and she opened the rear of her station wagon to store our pool accouterments. “Sorry about the mess.”

Opening the passenger door, the old Chevrolet spilled some papers from the supply of books, pencils, albums, and clothes that filled the behemoth. Once seated, she flapped her hand, motioning to roll down the window. “This car’s like ten years old with no AC, so it gets hot in here.”

I fumbled with 8tracks strewn about the floor as Marlene started the car and turned on the radio blaring “Moonlight Feels Right,” which she lowered the volume. “Do you like swimming?”

I wanted to say "no" but didn’t want to sound like a wimp, so I explained my propensity for drier activities being more of a land person, figuring once we arrived, I could avoid the swimming situation by focusing attention on the lions.

Arriving, we navigated the crowds milling around the pool until finding empty chairs near the lifeguard station. Quickly deducing the Lions Club had nothing to do with real lions disappointed but inspired a relaxing, albeit hot, lounge chair reading session. Marlene put her towel on her chair. “I’m going to talk to some friends. I’ll be right there.” She pointed to the edge of the pool where some teenage girls sat.

I lounged and read until Marlene returned sometime later. “You should go in; the pool is nice. It’s so hot out. Here put some lotion on so you don’t burn.”

Putting the lotion on, I couldn’t figure a way around going in the pool without looking like a wuss, and the hotness of the day made the pool inviting, and the more I worried, the more appealing the cool water seemed, so I went to the shallow end to make Marlene happy. No more than a few seconds in the shallow end, a group of five kids approached me with the largest at the edge of the pool’s steps. “You look like a girl with curly hair.”

Another kid stepped into the water and pushed me. “You’re an ugly fag.”

They laughed, so I exited the pool, but the boys appeared in front of me to again inform me of my gay, curly hair. The leader made a move feigning to hit me, which caused a flinch, raising hands to guard myself. “Don’t hit me.”

Stepping quickly between the boys and me, Marlene pointed to the kids. “What the hell? Go, get out of here. Stop picking on people.”

The kids ignored her. “Wussy needs a girl for protection.”

Marlene put her hands on her hips. “Simone says, ‘Oppression creates war.’”

Everyone, including me, stood for a moment in confusion. The moment passed, and the boys jeered again as Marlene folded her arms. “Fine. When I was thirteen, I promised my parents I wouldn’t dunk boys’ in the pool or beat them up, and to keep that promise –– Cheddar!”

Her outburst silenced the boys as Marlene smiled and motioned her head to the lifeguard chair behind them. Turning to witness a massive figure wearing red shorts and a whistle descending the back of the lifeguard chair, the boys watched as the teenage, herculean Adonis joined the group standing beside Marlene. “What’s happening, Mar?”

“Meet my little brother Cheddar. Cheddar, these boys won’t leave my friend alone.”

Cheddar flexed his arms in front of him. “Rah!”

The boys ran away, and Marlene laughed as Cheddar raised his fist proudly. “I Hulked them like Lou Ferrigno.”

She grinned. “Thanks, Cheddar.”

Cheddar looked down at me. “You’re okay.”

Marlene knelt beside me and went to put her hand on my shoulder, but I flinched and pulled away, making her lean back surprised by the reaction. “It’s okay. You’re alright. They won’t bother you anymore.”

I didn’t say anything or look her in the eye.

“Why don’t you come in the shallow end with me.”

“I can’t swim. I don’t know how.”

“Well, Simone says, ‘You can’t refuse to teach a person and then call them stupid.’” Marlene stepped into the pool, lowering herself to shoulder depth, swirling the water about her as if she controlled it. “To swim, you just need to know how to float.”

She held out her hands. “I won’t let go.”

I grasped her hands, she didn’t let go, and I learned to swim that day.

On the way home, Marlene parked the car in front of the pizza parlor. “It’s not that I don’t want to cook, but the tradition is to eat pizza after you swim.”

I looked at her enquiringly. “Cheddar?”

“Oh, he got his nickname when he was your age; he decided to eat all the cheddar cheese.” She waved her hand in front of her nose. “He stunk the whole house up.”

We purchased a pizza and returned home to watch Little House on the Prairie: Blind Journey before bed. Watching TV, Marlene pulled a slice of pizza to her plate. “You never really think about being blind, but it must be difficult at first trying to feel your way through the world. Or maybe it isn’t.”

I looked from the TV to her.

She raised her slice of pizza with a curious look on her face. “Maybe if all you know is darkness, then it’s comfortable and seems normal. You know what I mean?”

I nodded but didn’t know.

Awakened by noises from the kitchen early Tuesday morning, I rushed to investigate and found Marlene on her hands and knees cleaning yesterday's breakfast mess. Grabbing a towel and kneeling to help wipe up the grease, the floor soon cleared, and when finished, she rang the sponges in the sink. “You’re good at cleaning. I’m not so good.”

I related my cleaning experience with my grandmother as we wiped the stove and counter. Marlene shook her head while scrubbing the last spot of moisture from the counter. “I know you’re hungry, but it seems a shame to mess the kitchen up cooking breakfast.”

To alleviate her concerns, I revealed my knowledge of sandwich making and the use of sandwich glues. Retrieving bread, peanut butter, and jelly while Marlene opened the refrigerator for milk, she stopped to look at the gratitude list. “What’s this?”

I explained the gratitude list, and Marlene tilted her head, furrowing her brow. “That’s weird.”

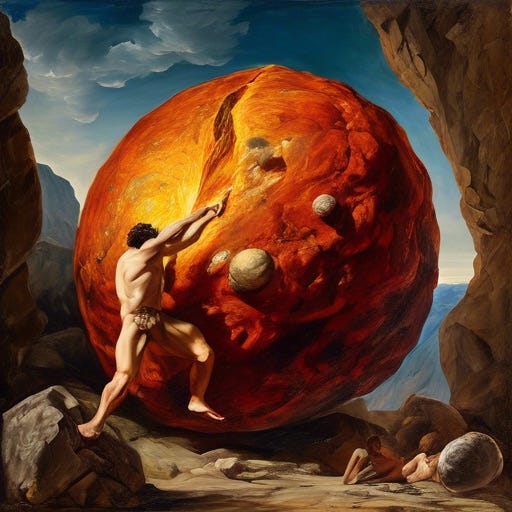

Finished with breakfast, Marlene carried dishes to the sink. “Wow, Simone was right when she said, ‘Housework is like the torture of Sisyphus.’”

“Who?”

“You don’t know Sisyphus?”

“No.” I meant Simone but felt equally curious about this Sisyphus person, and while we cleaned dishes, Marlene’s hands moved in a lively way as if directing a movie. “Sisyphus was known for his lying and self-aggrandizing. He was sly and clever but evil. He once even tricked the queen of Hades, Persephone, into letting him leave and-”

“What’s Hades?”

“That’s the underworld where the dead go.”

“Like hell?” I dried the dish she handed me.

“No, it’s not like hell, although it can be depending on if you’re good or bad. Well, Sisyphus was bad, and he was going to the bad part of Hades because he lied and bragged so much, Zeus-”

“Zeus?”

“Oh, he’s the head God, like the president. Zeus punished Sisyphus by making him roll a huge, heavy rock up a hill, and whenever Sisyphus neared the top, the boulder came racing back down the hill, and he had to start all over again. That was his eternal punishment.” Marlene turned off the water handing me the last utensil to dry.

“Why a boulder?”

Marlene stopped folding a dishtowel looking up. “You know, that’s a good question. I don’t know why Zeus chose that punishment. It seems like an odd punishment now that I think about it, but maybe that’s like the worst punishment, you know? Like having to endure something pointless, frustrating, and painful over and over.”

Finished the dishes, I went to my room to change the sheets, having forgotten in my hurry to get to the kitchen. The task of changing sheets routinely occurred as soon as I woke in the morning. After visiting with the Baltimorons, bedwetting worsened in frequency, but my urine concealment strategy hid the problem.

Bed-wetting is not easy to hide, requiring daily removal and replacement of the wet sheets with only dark sheets to make the urine less noticeable. Dirty sheets needed placement in the bottom of the laundry basket where my mother never noticed their wetness since I cleverly hid the urine by placing damp towels on top. Unlike my mother, Marlene took more interest in my morning routine and stood at my bedroom door. “I feel bad because you did all the work cleaning up. Let me help.”

I dropped to the floor, hiding the sheets in a ball, but too late, Marlene saw the wetness and stared for what seemed like a long time. Turning away from her, my face grew hot, and fear begged, “Please, please don’t tell my parents, please.”

A moment of silence ended abruptly with her sitting on the floor beside me. “Hey, you do have a lot of books. Have you ever been to the library?”

“My school has a library on the third floor, and in first grade, the teacher read us stories.” I struggled to remember the books until Marlene waved her hand to dismiss my words.

“That’s no fun. Let’s go to a cool library.”

Finished changing my bed, I cleaned and dressed while Marlene packed her bag with Tastykakes before departure to the library. The drive took us away from Westminster and into Baltimore City, which reminded me of the ride to my grandparents, but I didn’t recognize any streets or buildings. “Where are we going?”

Marlene glanced at me. “We’re in the city where the Pratt Library is located. Trust me, it’ll be worth it.”

Arriving, we found the library almost empty, and Marlene spoke with the librarian, who showed us to a section of enclosed desks that held tape recorders and record players. Marlene sat me at one of the desks with a record player and whispered as she plugged headphones in the record player. “I know you like Star Wars and Star Trek, but before all the special effects, there was different science fiction on the radio. My mom and dad showed me this when I was your age. They have a big collection of records like this, including other stories like Ellery Queen mysteries, which you can still hear on certain channels.”

Marlene carefully placed the needle of the record player on the large seventy-eight RPM vinyl, causing the headphones to crackle with Orson Wells, narrating across time, bringing to life the War of the Worlds. The next sixty minutes passed, lost in the ether emitted from the vinyl etched with Wells and Welles, ending with Marlene's lift of the needle at the record's end. “What did you think?”

I could only nod.

“We should get you a library card, so you can listen to the old broadcasts or check out books anytime you want.”

We filled out a form, and when finished, the librarian issued my first library card, which I studied on the walk to the car and as Marlene unlocked the door. “You know, we’re lucky because we can go sign up for a card and access all the books and records we want. My mom says most of the problems in the world are caused by people not reading. She says if people took the time to read, they would realize all past mistakes and benefit from that wisdom. She says it’s ironic we build these beautiful libraries offering all this free wisdom, and people choose to watch TV or spend money sitting in bars because they hate reading.”

I agreed and watched Marlene, who now appeared smaller, almost forced to look over the wheel as she drove. Wiping perspiration from her brow, her focus on the road held a visitant quality of peering into a place she alone could see. “My dad has a down-to-earth view of reading. He says, ‘If everyone read books, there wouldn’t be a whole lot of time for war.’ I think that’s cool, and it goes along with Simone’s view. Simone says books saved her from despair. Maybe they can save everyone from despair; you know what I mean?”

I did and nodded.

She steered, still peering into that unknown place. “I wonder why people don’t like reading. Maybe it’s because school can make books boring. There are so many books that are better than movies and television. I think people cheat themselves.”

I looked out the passenger window as the road filled with afternoon commuters. “Maybe being mean is more fun than books.”

I turned and found Marlene's stare, which she refocused on the road, saying, “Always remember, all the world’s wisdom is locked between the pages of books. All your answers are there even if you have to write them yourself.”

The fall of Skylab fascinated me since it was the first space station, and in my mind, confirmation of the coming space adventure, despite awaiting a fiery, uncontrolled reentry disintegration. Marlene and I prepared for this historic moment on Wednesday after cleaning messes made from further failed cooking attempts. There was some discussion of not telling my parents about the food fiascos, to which I assured her this would not be a problem since my parents discussed nothing with me. Having finally found a good babysitter, I had no intention of tattle-tailing, holding high hopes of Marlene taking the permanent babysitter position.

We retired to the backyard in the afternoon and set up my telescope. The sunny, clear day felt relaxed as the radio sang “Nights are Forever Without You,” which Marlene turned up a notch. When I finished setting up the telescope, I looked at her as she sat in the grass staring into an old book. “What are you reading?”

She looked up from the book in her lap. “Poetry. Do you read poetry?”

“Some in school.”

Marlene motioned for me to sit with her, and she shared the book. “This is Walt Whitman.” She followed the lines with her finger, reciting,

What do you think has become of the young and old men?

And what do you think has become of the women and children?

They are alive and well somewhere,

The smallest sprout shows there is really no death,

And if ever there was it led forward life, and does not wait at the end to arrest it,

And ceas’d the moment life appear’d.

All goes onward and outward, nothing collapses…

Her voice hummed like music, and for a moment, just a split second in time, all things connected in a singular motion with the grass, the elm tree at the end of the yard, the barn beyond, and even the sky becoming one in endless connectivity. The moment passed, and Marlene broke the silence. “Do you understand what he is saying?”

I didn’t understand the poem but felt it in her voice and loved it when she spoke. “He’s talking about life and how it is infinite. You know how they say space is infinite? So is life. Because time is infinite, there can never really be any death beyond the moment. Every possibility occurs in time. Everything exists in the infinite. If time is endless, then this moment happened over and over again. Sometimes better, sometimes differently, and sometimes worse. If I never saw you again, my leaving is just an illusion because we will be here again. Maybe happy or sad, maybe in the future, maybe in the past, but we will be here again sitting in the grass.”

I leaned my head against her and closed my eyes, fighting the lump burning the back of my throat. She put her arm around me. “You’ll be okay.”

After a short while, Marlene handed me Whitman’s book. “Here, you keep this.”

“It’s a library book?”

She winked. “It’s cool. I guess you don’t know. Books are the only thing you’re allowed to steal but only if you read them.”

“Simone says?”

“No. Marlene says.”

We watched the sky that night, hoping to see Skylab, which never appeared, but we ate Tastykakes, and Marlene related in her spirited, captivating way aspirations to be a writer. Sitting and eating, there beneath the perfect stars, I looked her in the eyes. “Marlene.”

“Yes.”

“Who’s Simone?”

Pulling into the driveway alongside Marlene’s station wagon, my parents exited and unloaded luggage as we watched from the living room. Marlene hugged me. “I’ll see you soon. Can you go to your room while I talk to your parents?”

Agreeing, I went to my room where I heard my parents enter the house but couldn’t hear their conversation with Marlene, which quickly heated into an incoherent voice ruckus. Anger rose from my stepfather, but Marlene stood her ground, raising her voice which surprised me, having never heard her rage. Hearing the slam of the front door, I went to the bedroom window and watched Marlene back her station wagon out of the driveway and speed away.

I stayed in my room fearing punishment, but my parents were surprisingly pleasant coming to say hello, and during dinner, they even asked if I had fun during their absence. The next few days passed in an unusual peace, and on the fourth day, a sheriff arrived at the house. Parking in the driveway, he exited his patrol car and approached the front door, where I lost sight of him but heard him enter the living room. Another muffled discussion occurred until my stepfather called for me to join everyone in the living room and motioned to the Sheriff. “Vince, please introduce yourself to the Sheriff.”

We shook hands, exchanging names, and he seemed nice, inquiring if I was okay, which I affirmed, then he turned to my parents. “Everything appears fine to me. You know how young girls can let their imaginations run away. Sorry to bother you. I thank you for your time.”

Marlene earned the titles of “stupid bitch” and “delinquent” from that day forward. My parents never spoke of her except in passing when the subject of crappy delinquent kids or dirty hippies arose in conversations, and I never mentioned her for fear of being grounded or worse. Sometimes in the middle of the night, I stared out the window, hoping to see her station wagon, wishing she would take me away.

Hiding the Walt Whitman book in my room, I tried reading it occasionally, but the book's difficulty took a long time to overcome, but whenever I opened Leaves of Grass, I thought of Marlene, and the lump rose in my throat, making me fight it for her.